© Fraunhofer HHI & FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg

© Fraunhofer HHI & FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg

Project LOReley

Releasing hydrogen more dynamically with a plate reactor

Binding hydrogen to a liquid and releasing it again when required: This is what LOHC technology is all about. The liquid organic hydrogen carriers have only been utilised in relatively small quantities to date. Experts from the LOReley research project, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, have now developed a new type of plate-based catalyst reactor concept for the hydrogen release process, which is intended to advance the technology.

Hydrogen, which is produced using renewable energies, is an important element of the energy transition. The energy carrier has a low density under normal conditions. It must therefore either be compressed under high pressure, liquefied at three-digit sub-zero temperatures or chemically bound at ambient pressure in order to be utilised effectively. One option for storing and transporting hydrogen is LOHC technology.

LOHC stands for liquid organic hydrogen carrier. These are oil-like liquids consisting of hydrocarbons such as benzyltoluene. Hydrogen can be bound to these carrier liquids and released again when required.

Hydrogen release requires a lot of energy

© FAU

© FAU

In the LOReley research project, experts from research and industry have focused on optimising the process for releasing hydrogen, known as dehydrogenation. "To release the hydrogen, reaction accelerators called catalysts and temperatures of up to 330 degrees Celsius are needed. Heat must be supplied to the process the entire time," explains project member Dr Patrick Schühle from Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU). "The less heat you have to provide for the process, the more efficient the entire LOHC technology becomes because you save energy."

Until now, a reactor with pipes into which pellets just a few millimetres in size were poured was used for dehydration. The pellets consist of porous aluminium oxide, in which the actual active metal platinum is deposited. When the hydrogen-loaded LOHC is brought into contact with the pellets, hydrogen is released. The experts in the LOReley project have now chosen a new approach and are relying on a plate reactor based on heat exchangers that are otherwise familiar from heating systems, refrigerators or industrial plants.

Ultra-short laser pulses increase surface area

© Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications, Heinrich Hertz Institute, HHI

© Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications, Heinrich Hertz Institute, HHI

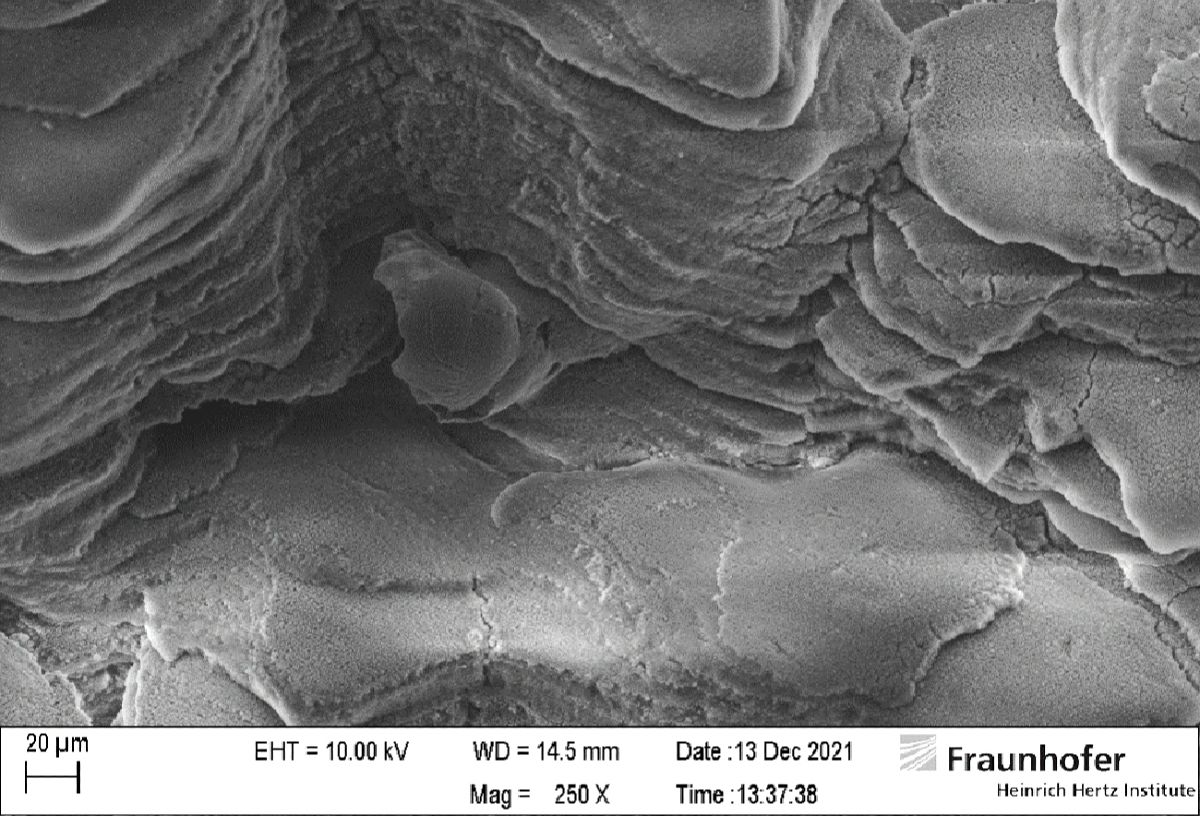

The researchers used the 20 x 20 centimetre aluminium plates from the heat exchangers and processed them with femtosecond laser pulses in a novel process. A femtosecond is one quadrillionth of a second.

"If you hit something with so many incredibly short flashes of light, it doesn't matter what material it is, it will vaporise instantly. In our case, the surface of the aluminium plate foams up, becomes considerably larger and very porous. It is like a sponge directly on the surface of the plate. In turn, the active metal platinum can be deposited in it. The previously flat heat exchanger plate has thus become a porous catalyst carrier," explains Prof Eike Hübner from the Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications, Heinrich Hertz Institute, HHI.

© Fraunhofer-Institut für Nachrichtentechnik, Heinrich-Hertz-Institut, HHI

© Fraunhofer-Institut für Nachrichtentechnik, Heinrich-Hertz-Institut, HHI

Surfaces designed in this way, which can take on a wide variety of properties, are not only relevant for LOHC technology. They could also be used in the chemical industry, mechanical engineering or medicine, for example.

The experts then allowed LOHC to flow over the plates of the heat exchanger from the participating company Kelvion PHE that were processed in the LOReley project. "The plate is heated from the back. This means that - unlike in a conventional reactor, where the tubes are heated with the pellets filled in - we have direct contact between the catalyst on the plate and the heated surface. This makes the heat transfer path shorter and the heat input very efficient. We have the heat where we need it," says chemist Eike Hübner.

The experts see a further advantage over the previous procedure in the fact that the catalyst is now firmly attached to the plate. "In the bulk reactor, the pellets can rub against each other and so the catalyst may be rubbed off as a powder. In the LOReley project, we have now developed a catalytic layer that is highly resistant to mechanical abrasion and vibrations," explains chemical engineer Patrick Schühle.

Dynamic operation was successful in the test

During the project, the experts tested the new catalyser reactor concept in the laboratory and on the premises of the participating company Hydrogenious LOHC Technologies, a spin-off from FAU. "We were able to operate our reactor for around 1000 hours in the project. It ran stably. There were also fewer by-products than with other coating processes. We still need to investigate why this is the case," says Eike Hübner. Dehydration of the LOHC can produce by-products, which is why purification of the liquid is necessary. The advantage is that the fossil carrier material LOHC is not consumed during the transport of the hydrogen, but can be reused over many storage cycles.

© HYDROGENIOUS LOHC TECHNOLOGIES GmbH

© HYDROGENIOUS LOHC TECHNOLOGIES GmbH

The experts were also able to show that they were able to double the hydrogen release rate within 15 minutes using the new plate reactor.

"The heat is not applied comparatively slowly across the entire volume of the reactor, but directly to the catalyst layer in a targeted manner. This flexibility in dynamic operation is relevant. Consider, for example, a gas-fired power plant that could also be operated with hydrogen in the future. If more electricity is needed quickly in the grid, 15 minutes is pretty quick. This also applies to mobile operation, for example in shipping, to quickly provide hydrogen for propulsion," explains Patrick Schühle.

The concept needs to be tested on a larger scale

During the research project, the experts were able to test their approach on a comparatively small scale. The reactor consisted of ten plates. However, to have enough power for a specific application, several thousand plates are needed. ‘The next step must therefore be to scale up our demonstrator and use it in real operation at a location where the hydrogen is needed,’ HHI researcher Eike Hübner explains. Only then will it be possible to say with certainty how well the reactor performs in terms of heat efficiency compared to the standard reactor. In addition, further research is needed to develop the catalyst further and to be able to largely dispense with the rare and expensive precious metal platinum in the future.

One challenge at the moment is that the market for the LOHC benzyltoluene needs to be scaled up further, as a study by the World Energy Council Germany recently pointed out. "In the project, we therefore focussed on developing a concept that is extremely easy to scale up in production. Ultimately, there are many parallel plates through which the air flows evenly. The same condition is therefore present in each plate gap. If a customer wants more power, the reactor could simply be expanded with new plates," explains FAU researcher Patrick Schühle. The project team can well imagine the use of LOHC technology, particularly on ships or in power plants that will be operated with even greater load flexibility in the future.